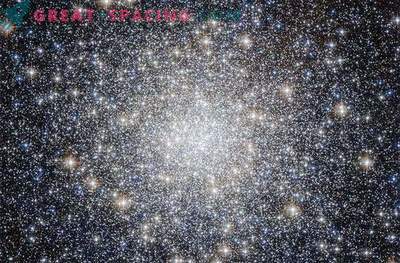

The red dwarfs — the star shorties of the galaxy — most likely are not very good for the development of terrestrial planets, say scientists launching new models of the formation of planets around various stars.

Astronomers have discovered a huge variety of alien worlds revolving around all types of stars, but stars of the same type, M-class dwarfs, stand out as places in which earth-like exoplanets could develop. In our galaxy there are many red dwarfs, and around many of them, as you know, small and (possibly) solid exoplanets are circulating. Red dwarfs live long, and perhaps there should be suitable solid planets rotating in the habitable zone of the star system, on which there is a good chance for the development of life?

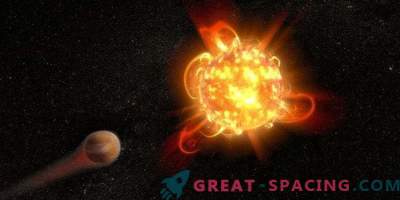

Unfortunately, there are some limitations for such a train of thought. Since the habitable zone around M dwarfs is extremely compact (these stars are smaller and therefore duller than our Sun, for example), any potentially habitable planet will have to rotate very close to the red dwarf. In this case, the solid planet is likely to fall into the "tidal trap" of the star, when the endless day will last on one hemisphere, while the other will freeze in the endless night - certainly not quite the "earthly type" in the classical sense. In addition, many of these dwarfs are considered active small stars that emit powerful flares that can destroy any form of life (as we understand it) before it can gain a foothold. Red dwarfs already look a little suitable for planets, really similar to Earth.

But, since the vast majority of stars in our galaxy are red dwarfs, of course, simply because there are so many of them, some of the star systems of red dwarfs have formed with the correct ratio of the matter of the planets and ideally located orbits. Can earth-like planets form in this case?

According to a new study from the Tokyo Institute of Technology and Tsinghua University, not quite.

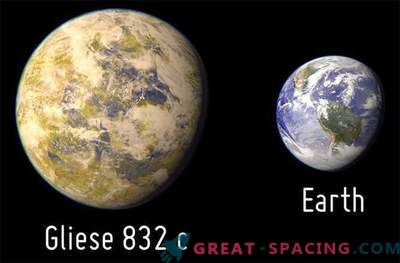

Researchers Shigeru Ida (Tokyo) and Feng Tian (Tsinghua) for the first time determined what “earth-like planet” means. According to this classification, such a planet should have about the same mass and size as the Earth. She should also have a similar ratio of water and land. Exoplanets with too little water are considered “desert worlds” (not enough water for the generation of species similar to terrestrial species), and those with too much water are known as “water worlds” (unstable climate and nutrient deficiencies). Ida and Tian found that exoplanets of the Earth type with the necessary proportions of water and land should have an extremely unfavorable ratio of the substance of the planets in the period of formation of this planet in order to form around the M dwarf.

While the red dwarfs are up to the main sequence, they are very bright and emit a huge amount of energy. Then they quickly move to a more calm and cold state. For any potential terrestrial-type planet that is being formed in a habitable orbit, the first years of a red dwarf’s life are complex. Because of their close proximity, these planets will roast, which will entail extremely strong consequences for their future activities.

After launching the model for 1000 stars with a mass of about 30% of our Sun (approximate mass of M dwarfs), 5,000 exoplanets were formed with a mass close to the mass of the Earth. However, only 55 of these planets were formed in the habitable zones of stars, and only 1 was formed with an “ideal”, as on Earth, water-land ratio. 31 planets in habitable zones turned into “desert worlds” and 23 turned into “water worlds”.