Graphic representation of the passage of planets in front of a star in the TRAPPIST-1 system

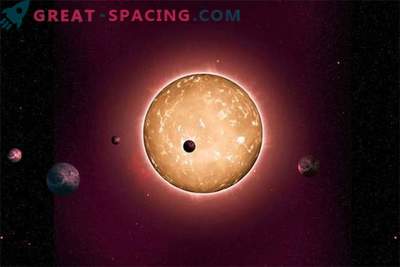

Red dwarfs may be small, but they may be crucial in finding exoplanets and possible inhabited alien worlds. According to recent studies, every red dwarf in our galaxy has at least one exoplanet and that a quarter of these exoplanets are within the inhabited zones.

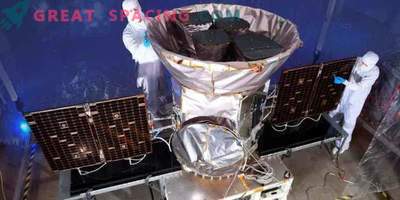

The search for new exoplanets in recent years has received a new round after the stunning discoveries made by the Kepler space telescope and the ever-increasing level of ground-based observatories. Last week, the discovery of new 715 exoplanets made by Kepler was reported. But this is only the tip of the exo-iceberg. With the help of improved observation methods, more accurate models and more accurate analytical tools, we can expect a new stream of discoveries.

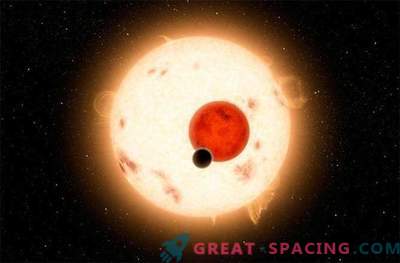

There is another intriguing target for astronomers - the lowly red dwarfs.

These cool, dim, small stars are half the size of our Sun, but, despite the fact that they lack energy, they compensate for the lack of life expectancy. Red dwarfs can save their energy for tens of billions and even trillions of years. If there was an inhabited world in orbit of a red dwarf, then it would have billions of years for development. Now astronomers from the UK and Chile are analyzing data from two high-precision telescopes specializing in searching for exoplanets - HARPS and UVES, operated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) and located in Chile.

These new studies combine data from both projects, taking into account the weak signals of exoplanets that would otherwise go unnoticed. The main part of the work was aimed at cleaning the signal from noise.

Both projects have discovered small oscillations of the star, rendered by invisible exoplanets spinning around it. Gravitational forces create a tiny shift in the orbit of a star, a shift that can only be detected with precision instruments. As expected, massive exoplanets spinning close to a star create a strong deviation, while small exoplanets make a weak one.

Although the Kepler Space Telescope specializes in searching for exoplanets, this does not mean that ground-based instruments, HARPS and UVES cannot participate in a joint search. It happens a little differently for them.

“We studied data from UVES and found some variability that cannot be explained by random noise,” says lead astronomer Mikko Tuomi from the University of Hertfordshire. "By combining this data with data from HARPS, we were able to detect potential candidates for the planet."