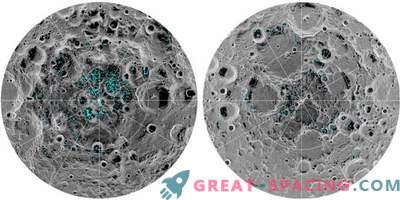

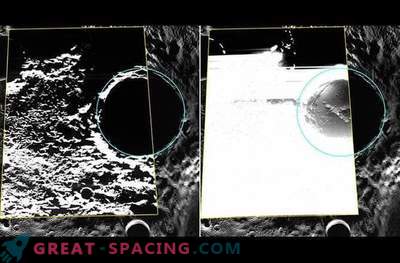

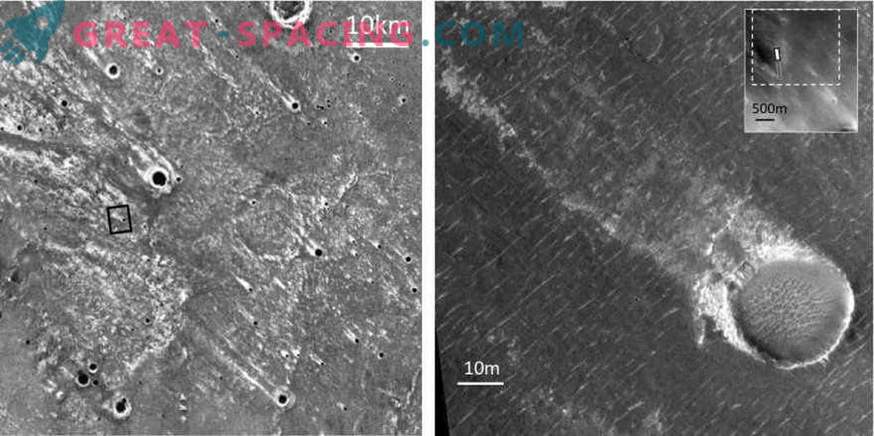

In the infrared image, strange bands are visible, extending from the crater of Santa Fe.

A few years ago, at a NASA photograph, Peter Schulz, a geologist at Brown University, found a lot of weird, distinctive bands from impact craters. They were unusual because they are only visible in infrared images taken during the Martian night.

With the help of geological observations, computer models and laboratory experiments, Schulz and graduate student Stephanie Quintana proposed a new interpretation of their education. They believe that during the crater strokes a whirlwind was created, resembling a tornado. Its speed reached 500 miles per hour, which made it possible to pick up dust and small stones, freeing up a denser layer of the surface.

“This equates to the F8 tornado,” said Schultz. “We’ll never see a second wind unless another blow occurs.”

The display in infrared images is due to the fact that the areas are contrasted with the temperature held. Brighter areas at night retain more heat than the rest of the region. Therefore, in visible light they can not see. Schultz studied shock processes for many years, experimenting with the NASA Vertical Cannon Series — a powerful cannon that fired projectiles at a speed of 15,000 miles per hour. Experiments have shown similar results.

Bands are often associated with smaller craters that existed before the appearance of large craters. This disrupts the flow of steam plume, causing the formation of vortices and loosening the soil. During the impact of an asteroid, tons of material (from the impactor and the surface) evaporate with lightning speed. Schultz's experiments showed that steam plumes move outward from the point of impact directly above the impact surface at very high speeds. If scaled, then on the planet it will be supersonic speed. When interacting with the Martian atmosphere, powerful winds appear.

But the plume and winds did not cause stripes. As a rule, they move slightly above the surface. But if the train stumbles upon elevated structures, it breaks the flow and forms strong eddies resembling tornadoes. It is they who clean out these narrow bands. Researchers have proven that these bands are always associated with elevated surface features.

Schultz believes that the strip is very useful if we want to establish the rate of erosion and dust deposition. Since they are formed simultaneously with large craters, their age can also be dated. But this is not the limit for research.

The found bands stretch around the craters for 20 km. But they do not appear in all craters. And here the most interesting is hidden. The presence of volatile compounds (for example, a thick water layer of ice) affects the amount of steam. That is, the strip can be used as a litmus test, which will show whether there was ice on the surface or in the depths at the moment of impact.